From Resources to Relatives: Rethinking Conservation

Across every conservation doctrine and management agency, the term "natural resources" is woven into the language. It describes the forests, rivers, and wildlife we strive to protect and provides a framework for their management. This language won critical support in the formative days of the conservation movement, paving the way for national forests, wildlife refuges, and clean water laws. Is it time for us to reassess our perspective and adopt a different approach, though? If we continue to view the natural world as inventory to be managed, even through the lens of conservation... are we really the good guys?

JOIN THE WILDERNESS GOODS COMMUNITY...

From Wealth of Nations to Conservation

The term "natural resources" didn't come from a park ranger or a field biologist. It was coined by a man commonly referred to as, "the father of capitalism." Adam Smith, the Scottish economist, published The Wealth of Nations in 1776 [no relation to another famous document drafted that year]. Smith's description of fertile soils, forests, fisheries, and mines as "natural resources" was a way to quantify and transform these elements into wealth.

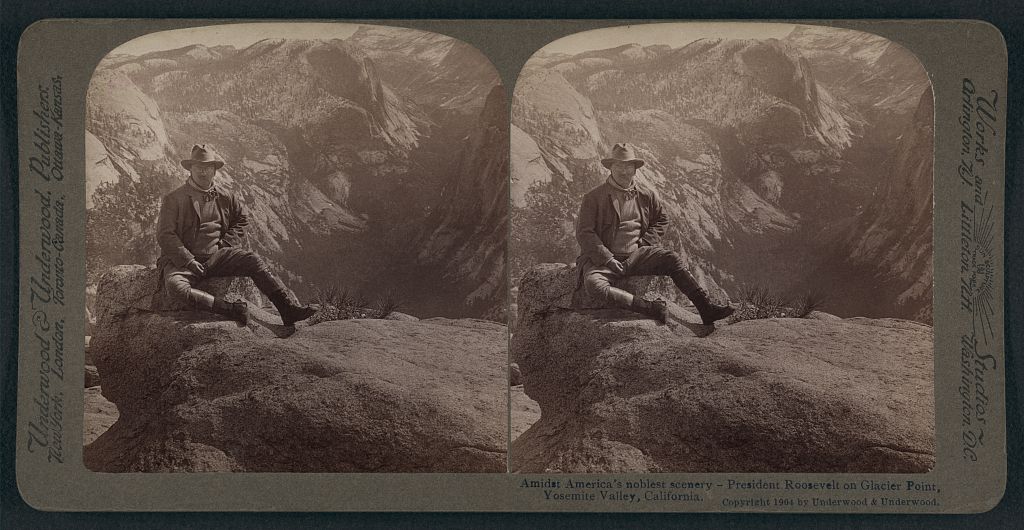

More than a century later, Theodore Roosevelt used that same language to brand the conservation movement, telling governors in 1908:

"The conservation of our natural resources and their proper use constitute the fundamental problem which underlies almost every other problem of our national life."

Gifford Pinchot, who Roosevelt appointed as the first chief of the US Forest Service, went further, defining conservation and the concept of multiple-use management as:

"... the use of the natural resources for the greatest good of the greatest number for the longest time."

That branding worked. It allowed conservation to fit within the framework of capitalism. However, it also tilted our perspective: forests and wildlife are the inventory, and we are the managers.

From Resources to Relatives

The "resources" frame didn't come only from economics. Western religion reinforced the idea, casting the natural world as something humans were given to use and subdue. That language of dominion shaped settler culture just as much as Adam Smith's economics. In contrast, Indigenous traditions spoke of reciprocity, gratitude, and kinship.

We don't need to cancel the term "natural resources," though. It's baked into law and policy. It gave us the National Park Service, the Wilderness Act, and the Clean Water Act.

But that same language limits our relationship with nature. As Robin Wall Kimmerer explains in her book Braiding Sweetgrass, "All flourishing is mutual." The practice of natural resource management often puts us above the system. Kinship - or recognizing your familial bonds and obligations to the natural world - places us within it.

The concept of kinship, or treating the natural world as a relative rather than a resource, isn't new. Indigenous cultures across North America — and around the world — have passed down kinship practices for generations. Their traditions serve as a guide and a reminder that gratitude, reciprocity, and obligation are not fringe ideas, but durable practices.

Both approaches are valuable. One works in policy. The other works in culture. Together, they empower us to measure not just what's sustainable, but also what's right.

When the House Gets Crowded: Population and Public Lands

But the landscape has changed. Before the arrival of Europeans, approximately four million people inhabited what is now the U.S. and Canada. Today, the population is closer to 400 million. Meanwhile, much of the land has been privatized or paved.

In a crowded house, obligations don't diminish; they grow. In a world where resources are increasingly scarce, the principles of kinship ethics become more important than ever. Closures, surveys, and quotas will always matter. However, most harm on public lands isn't a failure of management policy — it's a result of culture moving too fast.

So, what can you do? Start by asking different questions. Not "What can I take?" but "What do I owe?" The answers will look different for each of us — but they all point toward kinship. Skip the trail when it's muddy. Share your harvest instead of stockpiling. Plant something that feeds more than you. These small choices stitch us back into the system, one relative at a time.

JOIN THE WILDERNESS GOODS COMMUNITY...

Public Trust, Public Obligations

We often say that wildlife and waters are held in "public trust." However, trust is not just a doctrine; it is a behavior. It means packing out the trash you didn't drop, avoiding delicate trails even if the wildflowers are in full bloom, and directing dollars to habitat conservation even when animal populations appear stable. Building trust requires consistent action.

From Adam Smith's ledgers to Roosevelt's speeches, conservation has spoken the language of resources. That language saved the wild places that still remain. But to meet the challenges of a crowded house and a warming planet, we'll need more than management. We'll need kinship. The forest doesn't need our heroics. It needs our manners.